"Network Neutrality" advocates teach us that banning certain Active Queue Management (AQM) algorithms will result in greater freedom on the Internet. For example: Barack Obama wants to ban "Paid Prioritization," which Cisco calls "Low Latency Queueing".

Even folks interested in computers, but who don't build or run networks, seem to have some downright strange opinions. For example, when Netflix became a customer of Comcast, Ben Gilbert at Engadget claimed Netflix was "paying off" Comcast". When I buy a 50 Mbps link from Time Warner, instead of a 5 Mbps link, is the extra $30/month "paying them off"?

Net Neutrality and Freedom of the Press

American Journalist A.J. Liebliing famously wrote, "Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one." The folks who run routers and network links are something like the owners of printing presses. If our government restrict the rights of someone who owns a computing device which copies and transmits information, isn't that a violation of a basic right of humankind?

The folks who run routers and network links are something like the owners of printing presses. If our government restrict the rights of someone who owns a computing device which copies and transmits information, isn't that a violation of a basic right of humankind?

It's Distributed Computing, Not Common Carriage

Somehow, ISPs have been confused with Fedex. While a common carrier delivers an entire package or a working application, ISPs carry only packets. British Consultant and Scientist, Martin Geddes, argues strongly that the Internet is not "common carriage" like the postal service, but truly a distributed computing platform. It doesn't make sense to treat an ISP like UPS or the Royal Mail when "packets are merely arbitrary divisions of data flows. Broadband is fundamentally different from other forms of common carriage infrastructure. . . Packets are not people, and you don’t need to be ‘fair’ to them. There is no good karma in being even-handed to fragments of data flows in flight. It is only the fairness to people that we care about, which means only end user outcomes matter."

Netflix's Self-Destructive Taste in ISPs

Cogent is among the cheapest and worst of the "tier 1" ISPs. Netflix bought Internet access through Cogent, but unlike other web-hosting companies, Cogent doesn't expect to pay money to interconnect with other ISPs. Historically, this type of unpaid peering has been agreeable because customers (downloaders) and data sources (servers) were distributed roughly equally across the Internet.

So when Cogent needed bigger links to deliver Netflix data -- i.e., they wanted to install additional 10 Gbps Ethernet links to other ISPs -- they expected to get them for free and pass the savings on to Netflix. Cogent would pay for their router and their ports, but they expected Level(3), Comcast, and others to provide free access to router ports on their side.

It normally doesn't work that way. But because Cogent and Netflix had a business model built around the historical unpaid peering, it was very difficult for them to switch.

But why can't we stop Comcast from Mangling our Data?

But Netflix's choice of Cogent as an ISP and a naÏve business model -- has gotten conflated with Comcast's 2008 penchant for throttling Internet speeds. The FCC promised to enforce a ban on Internet throttling. "We need to protect consumers' access, said FCC Chairman Kevin Martin, a Republican. "While Comcast has said it would stop the arbitrary blocking, consumers deserve to know that the commitment is backed up by legal enforcement." So according to the FCC, "throttling" Internet access is already against the law.

Why is Netflix complaining? Because they don't want to have to pay much for their Internet links.

But Why do I Have So Few ISP Choices? I hate my ISP!

Many homes and businesses in America have three ways of getting Internet access:

- THE telephone company's voice-grade cable.

- Coax from the cable company.

- Wireless radio signal.

Telephone Wires, 1933 Edition

The telephone wires were built to support voice and voice only. But with the advent of "DSL," the same wires are good enough for a substantial Internet connection. There are more tricks coming to increase spectral efficiency, but for most folks, their Internet speed via DSL is between 3 and 6 Mbps.

Why is their only one telephone company who owns the wire going to your building? In the early 1930s, offering telephone service for all Americans became a national priority. But laying the wires to deliver all this service is quite expensive. Through the early 20th century, a bargain was developed, so that each telephone company:

- Had to promise to offer service to every address in its territory

- ...And would get a monopoly on some territory of the country

- And would be guaranteed some minimum profits.

That national priority allowed the monopoly, and that's why you have only one telephone company in most places.

If you're guaranteed minimum profits, then if your costs go up 10%, then you can raise your rates at least 10% with the government's blessing. So even as technology improved, the telephone companies had no incentive to minimize costs. Vendors took note.

Telephone Wires, 1996 Edition

In 1996, the telecom act allowed anybody to become a telephone company in the US. You had a to follow all the same rules, but if you did, you could buy Unbundled Network Elements including access to the copper wires that connected to each home. The logic was something like this: the telephone companies got a fabulous deal and government-sponsored loans for most of the 20th century, and the infrastructure built with that government assistance should be available to other players for more innovation.

Many ISPs and telephone companies have been built on those new rules. And the price of local service and of long distance in the United States has dropped precipitously, along with the stock value of telecom vendors like Nortel that were built on the shoulders of the overpriced telecom rules from the 1930s.

While the FCC made a good start at implementing these rules, they became convinced that they weren't really necessary. The telephone companies had no incentive to unbundled their network elements, and they found ways to get out of offering new services, like fiber links, to their "competitor" wholesale operators.

Dane Jasper of Sonic.net argues that reinvigoration of the 1996 Telecom Act would do a lot to bring more competition. "I call on the FCC to reconsider the decisions of that past era, and to take steps to reintroduce UNE-L (unbunded network element: loop) requirements, including access to available dark fiber, which is a critical backhaul component for competitive carriers. Copper unbundling is only fully viable when the middle mile fiber isn’t missing from the equation." Ironically, the laws requiring this are already on the books.

Cable Television Wires

I'm no expert on cable television vendors, but in my experience on a project in South Georgia I learned that the cable companies are granted a local monopoly, a franchise, which allows them to sell services to limited households, and gives them the "pole-attach" rights they need to run their cables around town.

Entertainment services were not a major priority initially. But because of the vast bandwidth requirements of serial, analog television, the technology used -- coax -- delivers enormous capacity for Internet access. In the FCC parlance, Cable Internet providers are considered "fiber" because they use fiber optic cables to deliver "Hybrid-Fibert-Coax" Internet to neighborhoods. The total bandwidth available over coax cable is well over 1 Gbps.

So it was local regulation, and the high cost of construction, that means most folks only have one provider for Oprah re-runs and for Coax-based Internet. My understanding is that there are no general rules preventing multiple coax or fiber providers from delivering service. If you can sign a contract with your local town, you can offer high-speed Internet there by building a new HFC network. If you have a small town of 10,000 homes, Cisco expects it to cost around $5.6 million (i.e., $561 per household-passed by the coax).

Wireless Internet

Wireless Internet, including LTE, is available to lots of folks as of my writing. But as of now, it's also relatively expensive to deliver a megabit over LTE or EV-DO. You can expect this to change and become a viable alternative.

Engadget and others have it wrong.

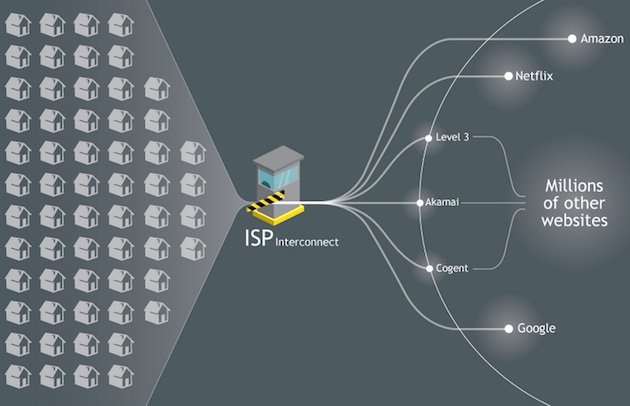

Engadget's deceptive depiction of ISPs suggests there's some beautiful spaghetti cable connecting your ISP to all the web sites. In reality, each party -- both each house, and each "website" has to pay the ISP to provide a service to it.

Engadget's deceptive depiction of ISPs suggests there's some beautiful spaghetti cable connecting your ISP to all the web sites. In reality, each party -- both each house, and each "website" has to pay the ISP to provide a service to it.Engadget seems to think that services like Netflix and Amazon are like the water we drink, falling freely from the sky, while ISPs are collecting it and charging you a fee. The model is completely wrong: Netflix and Amazon buy access plug into the ISP's equipment, just like homes and businesses do. And if Netflix doesn't buy enough access, they'll have slow Internet, just like you do.

Would Net Neutrality Raise Your Internet Bill?

Under modern telecom rules in the US, unlimited long distance talking is essentially free. Under the old rules, AT&T would offer a discount price of only $0.11 per minute -- but only during certain days, after certain hours.

We know that telephone service was drastically overpriced prior to the 1996 Telcom Act; we know this because the prices dropped as soon as technology could be developed to exploit the new freedoms under Federal Law.

It seems likely that placing additional restrictions on telephone service would be on-sided, guaranteeing only additional freedoms and guarantees to consumers. It would be a compromise, with ISPs promised guaranteed minimum profitability in exchange for certain difficulties.

And that compromise -- in the name of freedom -- would be likely to introduce a new era of overpriced telecom.

So, What's The Solution?

- I'm with Dan Jasper from Sonic. Let's get back to the principles of the 1996 Telecom Act as it was written -- applying to telephone companies.

- Local Governments should provide whatever incentives they can to get other providers to overbuild and provide additional service. But I don't think more taxpayer-sponsored network construction is necessarily smart. (But this is a good debate that we should have. Local governments have proven competent at other technical-engineering fields, like water delivery.)

- Federal, State, and Local Governments should require that no traffic throttling occur. And they should cancel contracts with ISPs that do throttle data.

- Consumers should aggressively shop for ISP options. Someday that 20 Mbps LTE that's already at your house may be the best option, so be ready to try it.